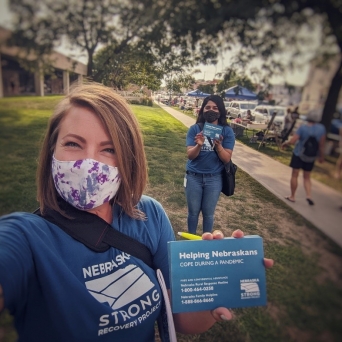

An effort to link helpers to Nebraskans struggling with 2019’s flood recovery has been extended and taken statewide to deal with a different kind of disaster: COVID-19.

The Nebraska Strong Recovery Project, funded during the post-flood phase with $6.7 million in federal grants, offers outreach to connect people in need with crisis counseling services and other resources.

With coronavirus, the methods have changed. Instead of going door to door in flood-damaged communities, outreach workers had to find ways to get the word out all across the state without making risky personal contacts.

“We had to find new and innovative ways to reach people, and we did. In fact, Nebraska was used as a model for other states requesting information,” said Mikayla Johnson, administrator of the Division of Behavioral Health at the Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services.

The recovery project is a collaboration of DHHS, the Nebraska Emergency Management Agency, the University of Nebraska Public Policy Center and the state’s six behavioral health regions. Seventy-three outreach workers are divided among the six regions.

The project plans to distribute 650,000 printed materials advertising, among other things, the Nebraska Family Helpline (888-866-8660) and the Rural Response Hotline (1-800-464-0258). The brochures so far have been distributed at outdoor events, during drive-by parades and at local businesses.

The project also is getting the word out through online coffee chats and YouTube videos, Facebook and Twitter and a website, nebraskastrongrecoveryproject.nebraska.edu.

Senior living facilities, where residents faced the isolation of lockdowns that ended visitations and excursions for their safety, have gotten a special focus.

One outreach worker in southeast Nebraska’s Region V, worried about people in isolation, decided to visit a retirement home weekly. She came across a woman sitting at a corner window, and they had “an instant connection.”

“It started with a wave and now it is the highlight of my week and she seems to beam with excitement when she spots me coming. We can have entire conversations through the glass.”

Lately, the woman has had more and more friends sitting with her at the window.

“It warms my heart to see that she is no longer alone at the window,” the outreach worker said. “Building connections and strengthening our communities is what our project is all about.”

A team in Region IV in northeast Nebraska found assisted living facilities and other programs clamoring for more materials for its Rock It Forward project. People in the community used donated rocks, paint, markers and brushes to paint the rocks, often including inspirational words. The rocks were collected and set out in walking areas for others to find and take.

The Nebraska Strong project also has found needs among frontline workers, including public health people doing contact tracing. They are notified of each new COVID case and are responsible for documenting, reporting and tracking all the cases in their area. They take calls at all hours. Some are clocking 70-hour work weeks.

“It’s amazing to see relief in the faces of worn-out staff when we say something as simple as, ‘How can I support you this week,’” one outreach worker said. “More often than not, we just need to be given permission to take care of ourselves.”

The Region V team now talks weekly with public health workers and helps prioritize ever-changing workloads. Stress-management and self-care workshops are planned.

In Region II in west-central Nebraska, an outreach worker described a young nurse and mother sharing how stressful life had become with all the uncertainties surrounding COVID-19. They talked about taking time for selfcare. Then the project team put a thank-you sign in the nurse’s yard. “She was actually overjoyed,” the outreach worker said.

Small business owners have been welcoming. A Region V outreach worker said a bar owner whose place was a hub for three small towns and area farmers welcomed her flyers and, while chatting, he opened up about his frustrations. He talked about the struggle to stay open when public policies discouraged crowds, the staffers lost because of quarantines, and the need to deliver dinners to nearby towns for elderly couples not comfortable dining in.

He was relieved to have a listening ear and to learn of resources for small business owners.

“His story makes my work more personal,” the outreach worker said. “I know that he is doing so much more for his community than just serving a great steak.”

Nebraska Strong’s goal is to double the outreach of the flood recovery effort, and it’s on track to do that over the next nine months, said Stacey Hoffman, senior research manager at the University of Nebraska Public Policy Center.

So far, crisis counselors have referred more than 500 people on to other services, including 132 for mental health services and five for substance abuse help, according to the Center. More than 200 were referred to community services such as COVID-19 testing, daycare to enable working from home or assistance with reduced income for such needs as utility services.

The hotlines’ 676 calls as of last month were up 50 percent from the flood recovery phase, a reflection of how different the disasters are.

“COVID is everywhere,” Hoffman said. “And we’re delivering services while the event is still happening.”

With holidays approaching and the prospect of traditional celebrations being disrupted, project workers expect to see stress in communities, with reactions varying from annoyance to major distress.

The Nebraska Strong Recovery Project has people who want to help. A program manager with the Nebraska Family Helpline said it’s been an honor to be part of responding to children and families struggling because of the pandemic. Long-time partners and new colleagues have worked together to provide crisis counseling.

“While most would agree it has been a terrible year,” he said, “we have been encouraged by the way Nebraskans have responded to the needs of their neighbors.”

by Deborah Shanahan | University of Nebraska Public Policy Center